The City of Lost Children (1995), directed by Jean-Pierre Jeunet and Marc Caro, is a darkly imaginative cinematic tapestry—part dystopian steampunk fable, part philosophical fairy tale, and entirely singular in vision. Set in a decaying seaside nightmare of a city, this French cult classic delivers a visual experience so rich and surreal that it feels like stepping into the dreamworld of a child raised on Grimm tales, rusted gears, and existential dread.

The plot revolves around Krank, a sinister, prematurely aging man who cannot dream. To stave off his own decay, he resorts to kidnapping children to steal their dreams through grotesque scientific machinery. His desperate pursuit of borrowed imagination creates the central tension of the film: What happens to a world that has lost its ability to dream?

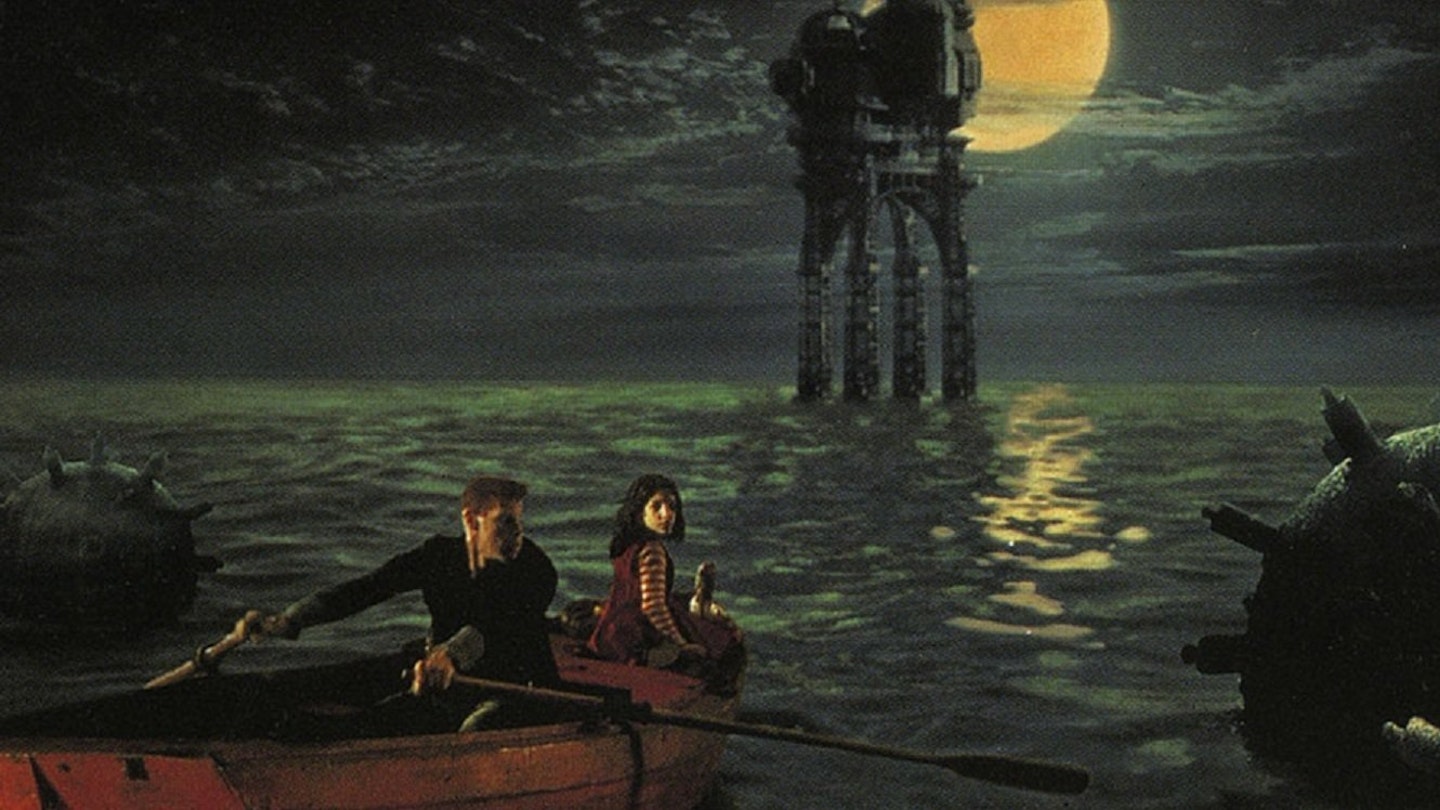

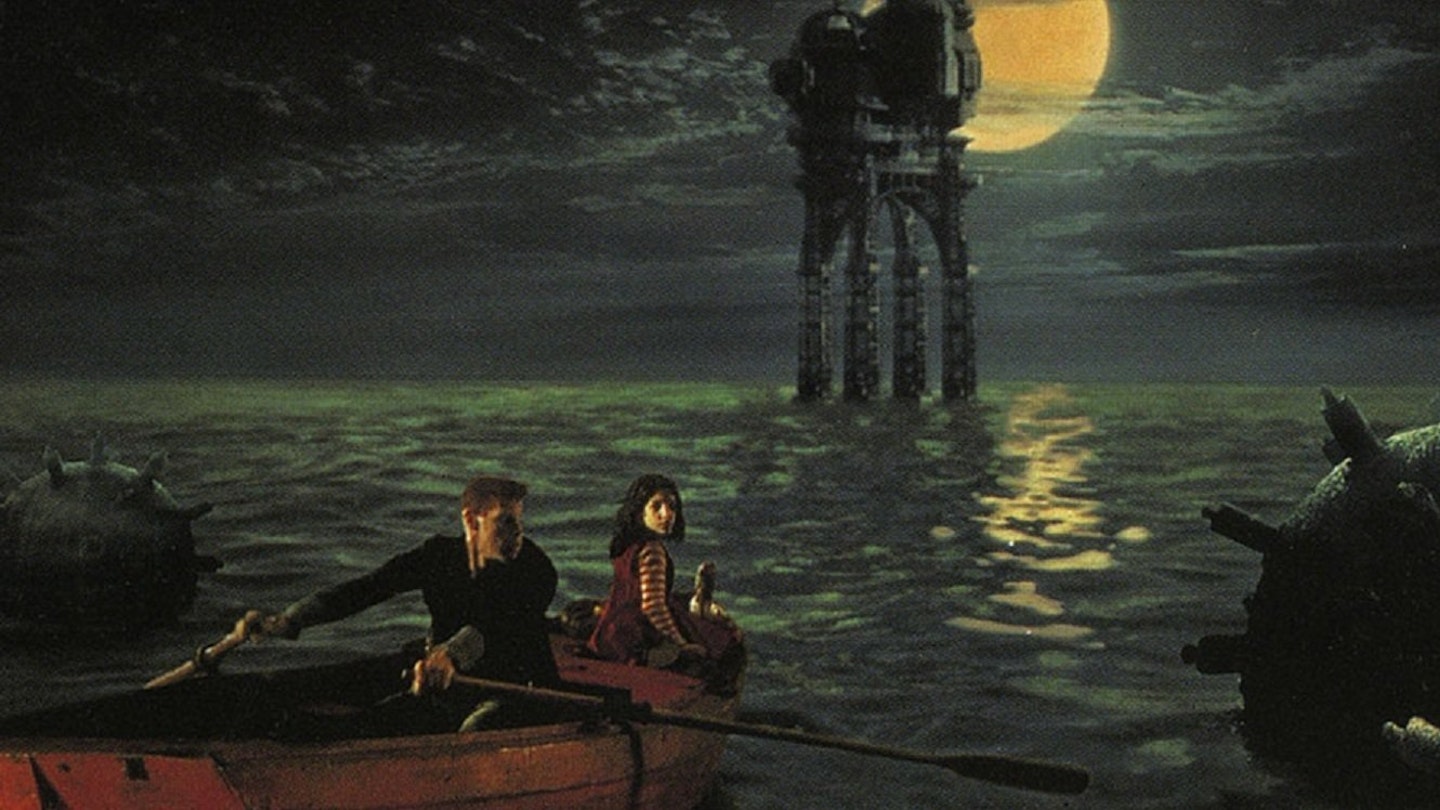

Our unlikely hero is One (Ron Perlman, quietly powerful), a hulking, kind-hearted strongman with the soul of a child, who sets out to rescue his kidnapped little brother. Along the way, he teams up with Miette (Judith Vittet), a street-smart orphan with a sharp tongue and an even sharper sense of loyalty. Together, they navigate a gothic maze of pickpockets, cults, cyclopean clone henchmen (played by Dominique Pinon), and mechanically-enhanced villains—each more bizarre than the last.

Visually, the film is astonishing. The cinematography by Darius Khondji (Se7en, Amour) paints the city in oily greens and browns, with shadows lurking in every corner and industrial steam constantly hissing in the background. The sets feel like Terry Gilliam crossed with Hieronymus Bosch—grimy, intricate, and absurdly detailed.

Angelo Badalamenti’s haunting score adds emotional weight, blending lullaby melodies with eerie undertones that reinforce the tension between innocence and menace. The music, like the film itself, oscillates between beauty and unease.

But The City of Lost Children is more than its aesthetics. Beneath the visual invention lies a melancholic core: a yearning for childhood wonder, a critique of mechanized society, and a reminder of the emotional and spiritual costs of a world without connection. The film probes the soul’s dependence on dreams—not just the kind we have at night, but the hopes, stories, and human bonds that give life its shape.

This is not a film for everyone—it’s strange, at times grotesque, and often deliberately unsettling. But for those who welcome its peculiar rhythms, it offers something rare: a glimpse into a world governed not by logic, but by imagination, where even the bleakest setting can flicker with magic.